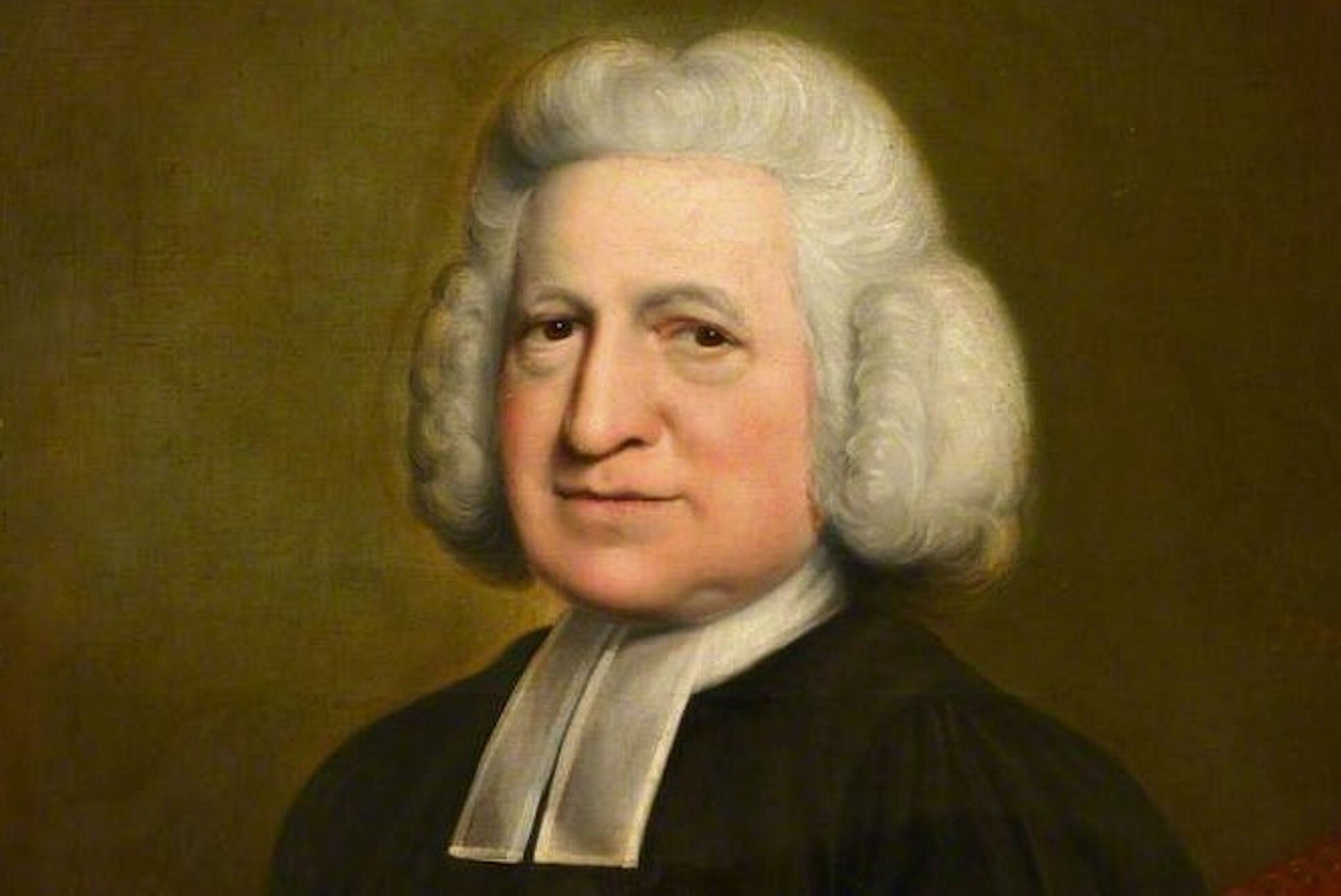

Charles Wesley

Charles Wesley was a prolific Methodist poet and hymnist writing during the eighteenth-century Christian revival. While Wesley is rarely mentioned in standard histories of the period, his immense body of work—including poems, hymns, and a fascinating journal documenting his time in America—interests scholars both for its religiosity and its first-hand account of a tumultuous period. Yet the immense quantity of his poetry and its uneven quality, along with its doctrinaire conviction and evangelical purpose, have generally compounded the difficulty of editing, evaluating, and interpreting Wesley’s work. Wesley’s poetry nevertheless provides invaluable insight into the important international phenomenon of the Christian revival, its theology, psychology, and understanding of the efficacy of useful verse.

Wesley was the eighteenth of Samuel and Susanna Wesley’s nineteen children, ten of whom survived childhood. He was born prematurely on 18 December 1707 in Epworth, and lay wrapped in soft wool for his first two months of life. When he was a toddler, the parsonage burned and the Wesleys narrowly escaped. Samuel Wesley divided his time between literary London and the parishes of Epworth and Wroot. In London he collaborated with his brother-in-law John Dunton on the “Athenian” projects and published long biblical works in Latin and English. Often in debt, Samuel Wesley relied heavily on the management and spirit of his wife. Susanna Wesley provided her many children with their early education and her absent husband’s parishioners with spiritual guidance. Competent in Latin, she presided over the schoolroom for six hours each day and led Bible study and prayer meetings in the kitchen.

When Charles Wesley was nine he was sent to Westminster School, where he lived with his eldest brother, Samuel. In 1721 he became a King’s Scholar and, in 1725, captain of the school. The following year he joined his brother John at Christ Church, Oxford, placing first among the Westminster candidates and earning a studentship. Charles was a brilliant student, held in high regard by his contemporaries. He was, as well, the first Methodist, so called for his extraordinary attendance at the weekly sacrament and his following the recommended method of study outlined in the Oxford statutes, and he persuaded several others to join him. When John Wesley, Fellow of Lincoln, Greek Lecturer, and Moderator of the Classes, returned to Oxford from a year at Epworth, he assumed leadership of the growing group, the Methodist “Holy Club.” The agenda expanded to include early rising, Bible study, and visiting condemned prisoners, as well as scholarship and sacramental observance.

When his father died in 1735, John, who had resisted pressure to succeed him at Epworth, fell under the spell of the remarkable General James Oglethorpe, prison reformer, founding father and governor of Georgia, and advocate for the cause of the Salzburg refugees. John agreed to go to Georgia as a missionary and persuaded Charles to be ordained and follow as Oglethorpe’s personal secretary. Amidst the terrors of five months of transatlantic travel, John and Charles befriended their fascinating fellow travelers the Moravian Brethren, learned German, and sang hymns, which would prove a lasting influence. Despite the unpleasantness of colonial Georgia, the brothers published their first hymnbook, a collection of seventy hymns, culled from various sources. In Frederica, Oglethorpe’s new town, Charles began his Journal (published in 1849).

The journal covers the twenty years from 9 March 1736 to November 1756. It includes snatches of hymns and other bits of poetry, but offers little insight into Wesley’s literary imagination or experience. But as an account of the revival and of one man’s experience of it, the book is a remarkable document. The wealth of Wesley’s experience is astonishing, encompassing high life and low, transatlantic travel and scholarship. At thirty he had seen more of life and the world than Henry Fielding, Alexander Pope, Jonathan Swift, or Samuel Johnson. One reads of the struggles in Georgia, the horror of slavery, and the perilous trip home by way of Boston; then of Wesley’s life as a celebrity, returned from America. Most important to the poetry are tales of his conversion and the conversions of hundreds of fellow believers, of countless sermons in countless places, of persecution, acclaim, and endless travel through rain and snow. He was often ill and treated gratis by sympathetic doctors by means of bleedings, purgings, and vomits. He got lost at one point, fell off his horse, and slept poorly. An ordained Church of England clergyman with an Oxford M.A., Wesley’s journal shows him composing thousands of hymns and sermons on the road.

Wesley’s hymns are indisputably his most important poetry. They were written for public musical declamation and they are at the same time richly personal but not private, designed to engage and direct each singer’s Christian devotional response toward a theologically appropriate end. As was customary, they were metrically limited to available tunes and imaginatively restricted by popular understanding. Wesley’s hymns are new and different from the hymns of Isaac Watts to the extent that Methodist theological ends were distinct: Methodists—who remained in the Church of England throughout Wesley’s life—sang no hymns in church worship. Rather, hymns as tools of revival and means of discipline bore a heavy weight of didactic responsibility.

The hymns of Wesley convey the grand adventure of the revival, the dangers and delights, the heroic struggles against Satan, and the ecstasy of love, as in “Christ the Friend of Sinners,” in Hymns and Sacred Poems (1739):

Outcasts of Men, to You I call,

Harlots and Publicans, and Thieves!

He spreads his Arms t’embrace you all;

Sinners alone his Grace receives:

No Need of Him the Righteous have,

He came the Lost to seek and save!

When Wesley sang these lines with prisoners in Cardiff (on 14 July 1741, as he reports in his Journal), twenty of them condemned felons, “many tears were shed.” While this is clearly not normative eighteenth-century verse, the precise rhetorical purpose and the tears of joy are familiar from moral-sentimental literature.

The Bible’s prodigal son was the model for conversion from sin, return home, and celebration. Methodists, like Saint Paul, lived with reference to the moment of complete conviction of personal salvation, as Wesley shows in “Free Grace” (in the 1739 Hymns and Sacred Poems):

Long my imprison’d Spirit lay,

Fast bound in Sin and Nature’s Night:

Thine Eye diffus’d a quick’ning Ray;

I woke; the Dungeon flam’d with Light;

My Chains fell off, my Heart was free,

I rose, went forth, and follow’d Thee.

As “Lover of my Soul,” Jesus then becomes the protector through the storm of life. The convinced Christian is Saint Paul’s soldier, armed with God’s strength for heroic encounter: “From Strength to Strength go on, / Wrestle, and fight, and pray, / Tread all the powers of Darkness down, / And win the well-fought Day...” (“The Whole Armour of God,” 1742). Indeed, as the title Hymns for Times of Trouble and Persecution (1744) suggests, the battles were not always metaphorical, and the well-known hymn “Ye Servants of God, Your Master proclaim,” included in that book, is “To be sung in a tumult.”

While the revival flourished, external threats and internal troubles multiplied. Parish pastors often refused their pulpits to the Wesleys, despite the brothers’ credentials, forcing them out of doors. Parish authorities sometimes resented the revived masses coming to church to worship and receive the sacrament. While high-church critics rejected the Methodists as fanatics, dissenting critics associated them with the Jacobites. (Yet the Wesleys invoked Thomas à Kempis in Ireland, preached an apparently Puritan piety to a seeming mob, despised predestination, and quoted Martin Luther on grace, all while insisting on the Anglican ordinances.) The Methodist Societies, organized across the kingdom, suffered a lack of stable leadership when Charles or John moved on. Simple people, full of new enthusiasm, were left to sectarian winds: Moravian, Calvinist, Quietist, or prophetic.

Wesley’s hymns, in this context, were supremely functional. In John’s preface to the definitive Collection of Hymns, for the use of the People called Methodists (1780), he describes his brother’s songs as versified divinity. The hymns prescribed and defined conversion, insisted on the free availability of grace, and rejected predestination. They invoked powerful images of Nativity, Crucifixion, Resurrection, and Second Coming, articulated appropriate responses, and insisted on the importance of Holy Communion.

The usefulness of hymns depends upon their accessibility, in word and idea, to common singers. It was also important that they provide popular, albeit devotional, entertainment. Many of Wesley’s hymns anticipate cinematic effects, as in “Thy Kingdom Come” (in Hymns of Intercession, 1758):

Lo! He comes with clouds descending,

Once for favour’d sinners slain!

Thousand, thousand saints attending,

Swell the triumph of his train:

Hallelujah,

GOD appears, on earth to reign!

The theatrical appeal was enhanced by new hymn tunes available to the Methodists. While Watts had been bound to the tunes of the metrical psalter, Wesley enjoyed access to the varied German tunes and the skills of contemporary musicians, including J. F. Lampe of Covent Garden.

The spectacular, noisy effect of some of Wesley’s hymns is very different from that of Watts’s controlled, baroque tableaux. Just so, the traditional love-longing of the Song of Songs is transformed by new metrical energy, for example, in Wesley’s poem “That Happiest Place” (Short Hymns, 1762):

Thou Shepherd of Israel, and mine,

The joy and desire of my heart,

For closer communion I pine,

I long to reside where thou art;

The pasture I languish to find

Where all who their Shepherd obey,

Are fed, on thy bosom reclin’d,

Are skreen’d from the heat of the day.

The new energy permitted a rush of metaphor.

Hymns also instructed believers in the Christian preparation for and response to death. In no other hymns is the conscious, manipulative artificiality of the genre so evident. Wesley insisted that since salvation was assured, death was devoutly to be wished. As he shows in “On the Corpse of a Believer” (Hymns on the Great Festivals, 1746), death was beautiful and corpses were to be envied:

Ah! lovely Appearance of Death!

No Sight upon Earth is so fair:

Not all the gay Pageants that breathe

Can with a dead Body compare.

With solemn Delight I survey

The Corpse, when the Spirit is fled,

In love with the beautiful Clay,

And longing to lie in its stead.

Wesley, in his journal entry for 5 February 1746, records how he visited “our sister Webb, dying in childbed: prayed with earnest faith for her. At hearing the child cry, she had broke out into vehement thanksgiving, and soon after fell into convulsions, which set her soul at liberty from all pain and suffering.” The next day “we sang that hymn over her corpse, ‘Ah, lovely appearance of death,’ and shed a few tears of joy and envy.” The hymn continues, instructing the singers in such envy:

To mourn and to suffer is mine,

While bound in a Prison I breathe,

And still for Deliverance pine,

And press to the Issues of Death:

What now with my Tears I bedew,

O might I this Moment become,

My Spirit created anew,

My Flesh be consign’d to the Tomb!

The tears of the faithful are incidental to their experience of death. Yet Wesley’s funeral hymns suggest certain limitations of the hymn genre. While the image in the hymn is what perhaps should be in one’s mind if one were perfect in the faith, such images can be repellent. Other generic limitations include the lock-step metrical patterning, the demand for doctrinal correctness, the insistence on perfectly clear language, and simple, traditional thought. Given such limitations, it is not surprising that some of Wesley’s unsuccessful hymns are good poems, or that verses he wrote without reference to singers better meet one’s expectations of lyric poetry.

“Dear, Expiring Love” (Hymns on the Lord’s Supper, 1745) failed as a hymn because it ignored the rules: its sentiments are not at all exemplary, its ideas are difficult, and its verse is metrically mixed. It belongs, nevertheless, to the fine devotional lyric tradition:

With Pity, LORD, a Sinner see

Weary of thy Ways and Thee:

Forgive my fond Despair

A Blessing in the Means to find,

My Struggling to throw off the care

And cast them all behind.

In April 1749 Wesley married Sarah (“Sally”) Gwynne, the twenty-two-year-old daughter of a wealthy, well-established family of Garth, Brecon. The cautious financial arrangements included securing for the couple Wesley’s share in the profits of the Wesleyan publications. They established their home in Bristol.

The poetry that Charles wrote as lover, husband, and father deserves consideration apart from his hymnody. Although many of these poems were eventually adapted and transformed into hymns, their differences are instructive. “Jesus, with Kindest Pity,” for example, was published in volume 2 of the 1749 Hymns and Sacred Poems. Wesley prays in the four stanzas for an earthly devotion that proves “the noblest Joys of Heavenly Love.” In the poem “Thou God of Truth and Love” (in volume 1) the lovers see their marriage as a providential means of their attendance on the Marriage of the Lamb. In “Two are Better Far than One” (volume 2) the poet celebrates the spiritual strength that comes from marriage:

Woe to Him, whose Spirits droop,

To Him, who falls alone!

He has none to lift him up,

And help his Weakness on;

Happier We Each other keep,

We Each other’s Burthen bear;

Never need our Footsteps slip,

Upheld by Mutual Prayer.

These poems effortlessly combine romantic love and Methodist piety.

Wesley’s “Hymn for April 8, 1750” (collected in Representative Verse, 1962) was an anniversary present, sent from London to Bristol. He begins with the opening lines of George Herbert‘s “Virtue“ (1633), immediately transforming them: “Sweet Day, so cool, so calm, so bright / The Bridal of the earth & sky! / I see with joy thy chearing light, / And lift my heart to things on high.” Sally is a guardian angel, sent by God, a heavenly gift, a bosom-friend: “‘Twas GOD alone who join’d our hands, / Who join’d us first in mind & heart, / In Love’s indissoluble bands / Which neither life nor death can part.” He will offer back the divine gift when he is summoned to live with God. “On the Birth-day of a Friend,” written for Sally Wesley, was published in Hymns for the Use of Families (1767). It uses the Song of Songs as a springboard:

Come away to the skies,

My beloved arise,

And rejoice on the day thou wast born,

On the festival day

Come exulting away,

To thy heavenly country return.

The birthday poem anticipates the joyful heavenly reunion of husband and wife after death.

Three of the eight children born to the Wesleys survived. His poems expressing paternal anxiety and grief are remarkable as poems and as documents in the history of the family. They are also noteworthy, as personal rather than exemplary poetry, for their generic difference from Wesley’s hymns. A prayer for his then-unborn first child took lyric form, and when the son (Isaac) and his mother later contracted smallpox, Wesley turned again to verse: “God of love, incline thine ear, / Hear a cry of grief and fear, / Hear an anxious Parent’s cry, / Help, before my Isaac die.”

The subsequent loss of his son provoked more poems, eight of them published as songs in the 1753 edition of Funeral Hymns. In “On the Death of a Child” Wesley tries unsuccessfully to force grief into otherworldly piety:

Those waving hands no more shall move,

Those laughing eyes shall smile no more:

He cannot now engage our love,

With sweet insinuating power

Our weak unguarded hearts insnare,

And rival his Creator there.

This is, clearly, a different grief from the hymn grief of “Ah, Lovely Appearance of Death.” Hymns for the Use of Families includes prayer poems for pregnant women and an elegy on the death of his second child, the infant daughter Martha Maria, in 1755. The baby had been distressed, “gaul’d and burthen’d from the birth, / Only born to cry and grieve.” The parents are left aching after the “balm of love.”

Also in 1755, distressed at doctrinal politics that were moving the Methodists closer to an open breach with the Church of England, Wesley wrote a series of eight carefully considered “Epistles” in heroic couplets. The poet’s brother John and their Calvinist friend and collaborator George Whitefield were among the intended recipients. Only the Epistle to the Reverend Mr. John Wesley was published that same year. In these lines Wesley undertook the delicate task of warning his brother, publicly and in print, of the dangers of separation. As it examines sectarian positions and advocates conservatism, the poem bears an almost unavoidable resemblance to John Dryden‘s Religio Laici (1682). The poem was widely published and republished. An Epistle to the Reverend Mr. George Whitefield remained in manuscript until after Whitefield’s death in 1771. The poem is a testimonial to restored friendship and common goals:

Our hands, and hearts, and counsels let us join

In mutual league, t’advance the work Divine,

Our one contention now, our single aim,

To pluck poor souls as brands out of the flame;

To spread the victory of that bloody cross,

And gasp our latest breath in the Redeemer’s cause.

This poem and Wesley’s “Elegy on the Late Reverend George Whitefield” (The Poetical Works, volume 6) were widely published in America.

The year 1758 saw the publication of Hymns of Intercession for all Mankind, concerned particularly with national and international politics. Frederick the Great was for Wesley “the Champion of Religion pure,” for whom the faithful prayed that he might avoid the Faustian dangers of pride and power:

Far from his generous bosom chase

That cruel insolence of power,

Which tramples on the human race,

Restless to have, and conquer more,

While bold above the clouds t’ascend,

The Hero sinks into a Fiend.

Hymns on the Expected Invasion, with Hymns to be used on the Thanks-giving Day followed in 1759. In 1762 Wesley published Short Hymns on Select Passages of the Holy Scripture, including five thousand selections, a project that had kept him occupied during a long year’s illness.

The sheer quantity of Wesley’s hymns, published and republished in dozens of collections, has tended to obscure the breadth of his interests and the diversity of his achievement as poet. He wrote political, doctrinal, occasional, and personal poetry as well as verses on riots and revolution, nursery rhymes, light satire, and elegies. Many remain in manuscript. His later poetry conveys his disgust at the loss of the American colonies, his profound disappointment in his son Samuel’s conversion to Roman Catholicism in 1784, and his bitterness at his brother John’s ordination of lay preachers, a move that ultimately led to the Methodist break with the Church of England. Wesley died on 29 March 1788. He was survived by his brother, his wife, and three children.

Three related sets of difficulties in thinking about Wesley’s poetry coalesce under bibliographic, ideological, and literary historical headings. The bibliographic problems compromise any responsible interpretation of Wesley and his contribution to the literary tradition. There is no definitive collection of Wesley’s work. The quantity of material is one problem: one count places Wesley’s output at 180,000 lines, contained in more than one hundred collections of verse and prose. The state of the material presents further difficulties: work by Charles and his famous brother is sometimes indistinguishable. Alterations, recombinations, new series, and new editions frequently frustrate researchers. Finally, there is the nature of the material itself: these are not 180,000 lines of epic, satire, or tragedy, but, for the most part, vast quantities of evangelical verse, communicating a specific vision of Christian experience.

Indeed, Wesley and his poetry are practically indistinguishable from the phenomenon of the Methodist evangelical revival, which brings up the second set of difficulties, the ideological. The revival, by nature, eschews indifference. The preachers and poets worked hard to provoke responses from their contemporary audiences. The responses ranged from eggs, stones, and angry rejection to swooning conversion, joyful enthusiasm, and transformed lives. Moderns react similarly to the provocations of evangelical discourse, either being repelled or engaged by the affective power of the movement. Many readers resist such manipulation and its seeming transcendence of critical intellect. Enthusiasts for Wesley’s verse, on the other hand, have invested it with extraordinary importance, studying the rhetoric, the diction, and the theology of his poetry, especially the hymns, in close detail.

Yet doctrinally committed literary scholarship sometimes means that conviction can predetermine critical judgment. Bernard Lord Manning, for example, wrote of how the 1780 Collection of Hymns “ranks in Christian literature with the Psalms, the Book of Common Prayer, the Canon of the Mass. In its own way, it is perfect, unapproachable, elemental in its perfection ... a work of supreme devotional art by a religious genius.” Most literary historians are unaccustomed to comparing scriptural and liturgical texts to poetry and rebel at the idea of perfection. However, Martha Winburn England has refused to “compare Blake to Wesley as a religious poet” since “Blake cannot stand the comparison.” Somewhat unusual literary values inform such a judgment, not least of which is the perception of Blake as a religious poet. Wesley’s staunchest advocates often seem to frustrate their own campaign to treat his poetry within the literary tradition.

The Methodist revival was nevertheless an undeniably important historical phenomenon in both Great Britain and the United States. Through its poetry one comes to understand this importance. One might also come to appreciate the poetry as significant itself, as a real contribution to the literary tradition. This is the third challenge, that of identifying a literary historical context for the poetry of Wesley. This work has begun: as a hymn writer, Wesley has repeatedly been compared to Watts. Martha England has argued for Wesley’s influence on Blake’s Songs, Milton and Jerusalem. More generally, Richard E. Brantley has traced interesting connections between John Locke, John Wesley, and the empirical method of English Romanticism. These efforts all look for connections beyond the Wesleys’ immediate era.

Charles Wesley’s poetic world will only come clear as scholars review and reinterpret the literature of the mid eighteenth century. Certainly biography, associated so closely with James Boswell and Samuel Johnson, was no less a concern of contemporaneous Methodist piety. A religious understanding that located a moment of conversion in each believer’s personal history would lead to recording and interpreting biographical detail as a matter of serious consequence. Just so, poetry written with a clearly persuasive, even extra-literary purpose was fitting in Wesley’s day. A literary history concerned with the larger social world of ordinary, suffering men and women could come to recognize the wealth of information and insight that Wesley’s poetry provides.