Out of Your Head and Into Your Body

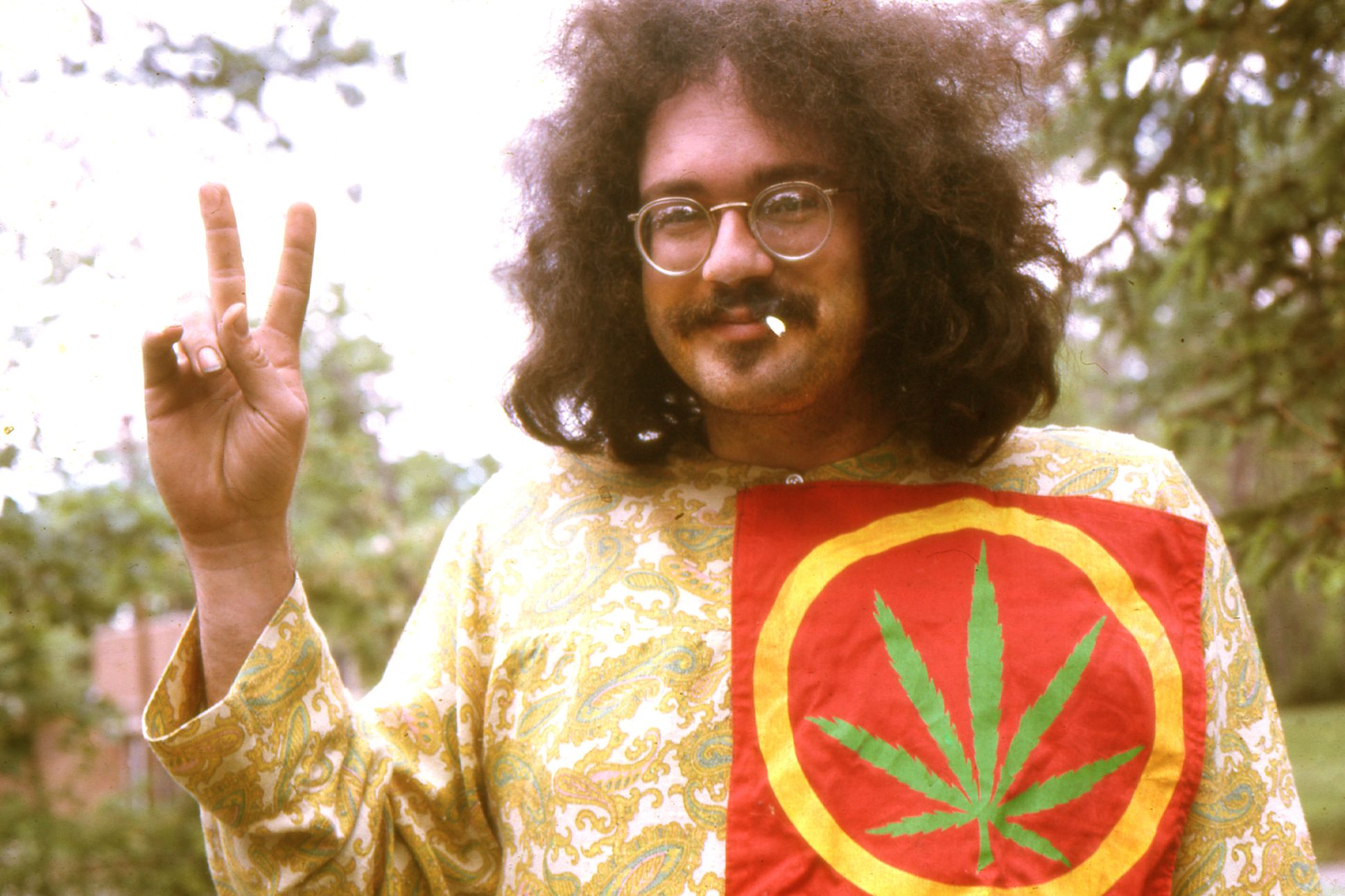

Six decades of revolution with John Sinclair.

John Sinclair learned about jazz and pot by reading books. A poet, activist, leftist publisher, journalist, and onetime manager of the Detroit protopunk band MC5, Sinclair grew up in a small town near Flint, Michigan, in the 1940s and ’50s. He discovered the Beats as a teenager, although it wasn’t always easy to find their books at the time. “You had to dig, dig, dig” Sinclair, now 82, tells me. “They had one bookstore in Michigan that you could get City Lights Books—Bob Marshall’s in Ann Arbor—and I had to send away for Howl by Allen Ginsberg and Gasoline by Gregory Corso.”

As for jazz, Sinclair first encountered that in On the Road but “never heard [the music] until a couple of years later. I was looking for it, but I didn’t know where to find it,” he says. “I wanted it bad, just like reefer. I read about marijuana, and I wanted some so bad, but I had no idea how to get it.”

He got both eventually.

Sinclair has devoted himself to marijuana advocacy for decades and is partly responsible for early decriminalization laws in Ann Arbor and Holland, Michigan. In his honor, multiple strains of marijuana and seeds—including a strain from Amsterdam’s Cannabis Cup, where Sinclair served as High Priest in 1998—are named after him or groups he formed in Detroit.

If these stoner homages come across as unserious, that’s not the case for Sinclair’s broader revolutionary agenda. He has long recognized how drug criminalization is connected to larger systems of oppression, and he has used poetry (but not only poetry) to reveal the workings of these systems, as in “It’s All Good,” a poem from Mobile Homeland:

Because the war on drugs

Is about building a police state.

The war on drugs

is about building prisons

& filling them up

Sinclair’s wide-ranging career has spanned more than 60 years, but he’s likely best remembered for the massive John Sinclair Freedom Rally that followed his arrest for marijuana possession in 1969, after which he was sentenced to nine-and-a-half to 10 years in prison. The rally—held on the campus of the University of Michigan in December 1971—featured performers and speakers including Ginsberg, Stevie Wonder, Yoko Ono, John Lennon, Phil Ochs, Jane Fonda, and Black Panther cofounder Bobby Seale. In his speech at the rally, Seale advocated for expropriating the capitalist system:

[That’s] the only way I know to start attacking the monster of capitalism. A monster charging people money for everything they get. We’re saying the music is free. The life is free. The world is free. And if it ain’t free, let’s start getting our chains off now—the psychological chains and the chains of oppression. Let’s get it off now. Let’s move the chains off of us. Because if we don’t move the chains off of us, they’re gonna annihilate us. They’re gonna annihilate us by polluting the earth. The capitalists and the fascists, they’re gonna do us in. We’re saying the universe belongs to the people. The moon belongs to the people. Mars belongs to the people and the people belong to the people. All power to the people.

The activist Keith Stroup also attended the event and later recalled:

People were not only smoking joints openly and passing them around, but several people, including one sitting near my seat, had quantities of marijuana sitting open on their laps, freely rolling joint after joint, to make sure everyone who attended could get high for the occasion. It was the first time I recall ever seeing such mass civil disobedience, and it was empowering to experience. Tens of thousands of people openly smoking marijuana and no one being hassled by the police.

Three days later, Sinclair was released on bond, and in March 1972, the state’s marijuana laws were declared unconstitutional and Sinclair’s conviction was overturned.

By that point Sinclair had been arrested multiple times on minor drug charges, though these convictions were about more than marijuana alone. As a major figure in leftist movements, he was increasingly surveilled and harassed by both local police and the FBI. Sinclair had also helped found three countercultural organizations: the Detroit Artists Workshop, its outgrowth Trans-Love Energies, and the White Panthers, a radical antiracist group inspired by and seeking to support the Black Panthers. He used his role as manager of MC5 to, in the words of musician Cary Loren, “freakize American youth,” turning them on to the revolutionary cause.

Sinclair’s use of music as a revolutionary instrument was part of the White Panther Party’s “total assault on the culture.” As the group’s Minister of Information, Sinclair wrote that music “makes use of every tool, every energy, and every media we can get our collective hands on.” In the 1968 White Panther Statement, published in the Ann Arbor Sun, he adds that “rock and roll music is the spearhead of our attack because it’s so effective and so much fun.”

“We had a lot of nerve, and we were on acid,” Sinclair tells me. This matches the Panthers’s statement, which presents a self-image of “LSD-driven total maniacs in the universe” who would “do anything we can to drive people crazy out of their heads and into their bodies.” With MC5, Sinclair had a way of doing just that—access to huge audiences of young people and a “guitar army” who could spur the movement forward.

Turning to music as a means to spread the message mirrors Sinclair’s own path into radical politics, which started with jazz. In our conversation, Sinclair recounts how he was introduced to jazz through literature, but once he heard the real stuff, he never looked back. In the early 1960s, he hosted a radio show from his dormitory on the campus of Albion College, which he attended for two years before transferring to what is now University of Michigan-Flint. He played mainly rhythm and blues, but one day another student showed up at his dorm and asked, “man, are you hip to jazz?” Sinclair replied that he wasn’t, not yet, so the other student “took me by the arm and dragged me up to his room on the second floor and played me this record by Miles Davis. I was hooked right then. That was enough for me.”

For the next few years, Sinclair became a student of the genre, spending time in the listening booths at local record shops. “I would take about ten records into the booth, and I’d listen to one and read the backs of the other nine.” His early poetry reflects both of these experiences—listening and reading—as Sinclair began to incorporate everything he was learning into his own creative productions.

In 1964, Sinclair moved to Detroit to attend graduate school at Wayne State University, where he was studying American literature. He began supplying the campus with weed and hosting informal gatherings in his apartment, where friends would hang out, get high, “listen to records and talk about music, poetry, and books.” Out of these gatherings was born the Detroit Artists Workshop, which Sinclair founded with his soon-to-be wife, the photographer Leni Sinclair (née Magdalene Arndt), along with more than a dozen other Detroit-based artists, musicians, and writers. This was before the full flowering of the hippie era, and in a piece commemorating the group’s 10-year anniversary, an unnamed Workshop member recalls “REALLY being an oddity” during a time when there were “no antiwar demonstrations, and [no men] had hair longer than John Wayne’s.”

The group ran the Artists Workshop co-operative, a communal living compound consisting of six houses near Wayne State and involving artists from the Cass Corridor neighborhood, then a poor, bohemian area of Detroit that attracted countercultural figures. The Workshop printed all kinds of publications, from manifestos to poetry to music journalism. And they hosted regular free jazz concerts and poetry readings on Sundays.

The Artists Workshop Press published Sinclair’s collection This is Our Music (1965), which includes a suite of poems for John Coltrane entitled “Four for Trane.” This short series takes its name from an album released that same year by saxophonist Archie Shepp, one of the performers who played at the Sunday concerts. “Homage to John Coltrane” combines Sinclair’s experiences listening to jazz with the reading he’d been doing in literature, and in those record store booths perusing liner notes as he developed his ear:

“you are sorry you are born with ears”

or you are sorry. yr

ears. how they can become

the stuff of such lies.

how a man can

stand, & fall. Stand. “a

coil

around things.” A

sound (or a test

of what music

can bear. A

SCREAM

for the time

The piece opens with a line from A. B. Spellman’s poem “John Coltrane: An Impartial Review” and includes another quotation from the same poem in “a / coil / around things.” Later, Sinclair quotes the liner notes to Coltrane’s 1964 Live at Birdland album, which were written by Amiri Baraka (then known as LeRoi Jones).

Sinclair often deploys this type of intertextuality in his writing, and other examples from the era show him returning to some of the same influential figures. For instance, Sinclair's poem "The Destruction of America" (also from This is Our Music) was included in the anthology For Malcolm: Poems on the Life and Death of Malcolm X, published in 1967 by Detroit’s Broadside Press. Dudley Randall founded Broadside in 1965, and it became the nation’s largest publisher of Black poetry. One of the few white writers included in the anthology, Sinclair's poem indicates it is "after" Baraka's novel The System of Dante's Hell (1965), and in the contributor notes for the Broadside anthology, Sinclair writes, "like Archie Shepp said about his music, all my work is for Malcolm."

“Homage to John Coltrane,” meanwhile, is dedicated to jazz trumpeter Charles Moore, Sinclair’s roommate and a cofounder of the Detroit Artists Workshop. It was Moore who first invited Sinclair to read poetry with a band, something Sinclair continued to do for the rest of his life. The dedication reads: “For Charles Moore (who helped pull my coat).” Pulling someone’s coat is slang for alerting someone, letting them in on something. The phrase also echoes earlier lines from the eponymous poem in This is Our Music, in which Sinclair writes:

& they stole our

coats

(thank god

before we could

turn them

Here, Sinclair begins to hint at what jazz would do for him: namely, become a lifelong passion and a medium for poetic collaboration. But jazz would also be responsible for Sinclair’s awakening to the Black revolutionary cause, which he arrived at by tuning in to Black music.

Sinclair founded the White Panthers with Leni Sinclair and the activist Pun Plamondon in 1968. The Party statement, penned by Sinclair, acknowledges that “the actions of the Black Panthers in America have inspired us and given us strength, as has the music of black America.” The statement explicitly names Coltrane, Shepp, and Sun Ra, as well Baraka, Malcolm X, Huey P. Newton, and Bobby Seale.

The White Panthers’s founding came on the heels of Detroit’s 1967 uprising, a five-day insurgency that started when police arrested 82 Black people during a single night’s raid of a “blind pig” (an unlicensed bar). Protests, and, eventually, fires followed. Governor George Romney, together with President Lyndon B. Johnson, sent thousands of National Guard and US Army troops into the city to “quell” the turmoil—which they ultimately did at great cost. Forty-three people were killed, hundreds were injured, more than 7,000 were arrested, and more than 1,000 buildings were burned. Many white Detroiters were horrified by the violence and fled the city by the tens of thousands.

Sinclair characterizes the rebellion as an acute reaction to the systemic racism built into all aspects of public and private life in Detroit, as he states in “Motor City is Burning”:

this was a rebellion,

an uprising against racial oppression,

segregated housing,

the greedy landlords & businessmen

who controlled their environment,

the denial of economic opportunity,

the refusal to provide proper education

& the relentless persecution by the police—

no relief in sight,

nothing to look forward to,

no way to get ahead—

why not burn the motherfucker down?

Earlier in the poem, Sinclair writes that “the damage / was carefully directed / at the objects of their oppression,” depicting the burning as targeted rather than indiscriminate.

Just a year after the rebellion, Sinclair recalls how “when [Plamondon] was in jail for marijuana . . . he read an interview in a magazine with Huey P. Newton. They were asking him what white people could do support the Black Panther Party.” While it’s not entirely clear which interview Plamondon read, Newton made various statements to this effect at the time. For example, the Students for a Democratic Society published an interview with Newton in August 1968, three months before the White Panthers were formed, in which he says that the Black Panther Party is “an all black party” but also acknowledges a role for the white radical to “aid us in our freedom.”

About the Black Panther Party, Sinclair tells me, “I was wishing they were running everything.” And Sinclair understood at the time that what he needed to do was “turn on white people to the idea of Black liberation” because white people, as Sinclair emphasizes, were the problem.

Reading, music, and his experiences in 1960s Detroit were all pathways into Sinclair’s coat-pulled new era. But the circumstances around the White Panthers’s founding also speak to the way that time in prison on drug charges influenced Sinclair’s radical development and that of other white outsiders, who came, as Newton describes in his interview with the SDS, “from the middle class”—“children of the beast” who would grow up to turn on the system that birthed them.

In jail and in prison, Sinclair and his collaborators were exposed to the most blatantly oppressive arm of the state and began to communicate the need, as he writes in the White Panther Statement, to “free everybody from their very real and imaginary prisons.” They worked to do this through all available avenues, including writing and publishing.

After arriving in Detroit, Sinclair established a robust DIY practice as a printer, publisher, and writer of many genres. “We didn’t have any money, see, so we had to be creative and reach people,” Sinclair tells me. “That’s why we started mimeograph publishing. We could afford that.” Leni Sinclair worked at the time for Otto Feinstein, a Holocaust survivor and anti-fascist professor of political science at Wayne State, and the Sinclairs were able to print on a mimeograph that he gave them access to near campus. (Sinclair also credits his friend, the poet, musician, and activist Ed Sanders, with inspiring this work.)

In addition, Sinclair was music editor for Fifth Estate, which, like the Workshop, was run out of Detroit’s Cass Corridor, and he wrote for other outlets including The Warren-Forest Sun (later renamed The Ann Arbor Sun), which started as a mimeograph newspaper put out by Trans-Love Energies. For its first issue, Sinclair conducted and published an interview with Sun Ra. Later, The Sun published Sinclair’s writing as White Panther Minister of Information, and eventually as Chairman.

This active publishing operation allowed Sinclair and the White Panthers to spread their message, which, as the Party’s 1969 10-Point Program outlines, boiled down to freedom: “to free all structures from corporate rule;” “free time and space for all humans;” “the freedom of all prisoners held in federal, state, county or city jails and prisons;” “the freedom of all people who are held against their will in the conscripted armies of the oppressors;” and “free land, free food, free shelter, free clothing, free music, free medical care, free education, free media.” This agenda borrows heavily from the Black Panther’s 10-Point Program from 1966, which speaks to the circulation of Black Panther materials and their influence on the white radicals in Michigan.

In 1969, the same year Sinclair was sentenced to nine-and-a-half to 10 years in prison, the Detroit Artists Workshop sold a printing press to a couple of their affiliates—the painter Ann Mikolowski and her husband, the poet Ken Mikolowski. This 1904 press became the backbone of another major print operation in Detroit: the Mikolowskis’s Alternative Press. With Sinclair and the Panthers using their print operations, among other activities, to advance a program of revolution, other radical printers also circulated materials to and from Sinclair, including while he was incarcerated.

The Mikolowskis’s Alternative Press printed and mailed a significant amount of poetry to Sinclair during the period he was held in a remote prison in Marquette, located in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. The facility was approximately 450 miles from Detroit, where Sinclair’s pregnant wife and baby daughter were living. Sinclair had been moved to the isolated location from a prison in Jackson (about an hour from Detroit) over what Perry Johnson, then deputy director of the Michigan State Bureau of Prisons, called his “disturbing influences.” The Ann Arbor News reported Johnson saying, “We simply can’t afford to permit the setting up of a resistance movement” inside the prison walls.

But the move to Marquette didn’t stop Sinclair’s organizing. There, he was involved with a strike by Black inmates who wanted to see a Black studies program instituted in the prison (ultimately, this resulted in Sinclair being moved back to Jackson, where he was held in solitary confinement). During his time in Marquette, Sinclair continued to organize outside of the prison walls as well, through the post and via alternative media.

His 1969 poem “The Alternative Press” is, he tells me, an homage to the Mikolowskis and what they were doing with the antique letterpress they received from the Artists Workshop. What they were doing was: printing a lot of poetry and giving it away for free. In his poem, as in the White Panther’s 10-Point Program, Sinclair focuses on the question of what it means to do things for free, to try to be free, and to make a life of art outside the status quo:

And we will press that alternative

in the face of whatever it is

would not have us free—we will press it,

and press it,

until our lives themselves

become the poem

Later this year, Detroit’s Ridgeway Press will publish Sinclair’s Collected Poems: 1964–2024. The book doesn’t include this poem, nor work from Sinclair’s Prison Diary, a collection of poems he wrote while incarcerated in Marquette between 1969 and ’70. In his introduction to the forthcoming volume, Sinclair writes that the Prison Diary is “buried in my archive at the University of Michigan” and isn’t something he wants to revisit. Other prison writings can be found in Sinclair’s Guitar Army (1972), and additional poems he published with the Alternative Press will be available in my forthcoming book, Detroit’s Alternative Press: Dispatches from the Avant-Garage. The Collected Poems doesn’t include many of Sinclair’s blues and jazz poems either, but some of these can be heard on his more than 30 albums of recorded poetry, available on Bandcamp via the John Sinclair Foundation website.

Even so, the career-spanning Collected Poems features more than 150 poems and attests to the fact that Sinclair has been actively writing, reading, and listening for a lifetime. After he left Detroit in 1991, he lived in New Orleans for 12 years, and his collected works feature many collaborations he developed there with local musicians. Later, he lived in Amsterdam, where he founded Radio Free Amsterdam. Coming full circle from the days of playing records in his dorm at Albion College, Radio Free Amsterdam produces “weekly blues, jazz or free-form programs for college or community stations” and anyone around the world can listen.

In Guitar Army, Sinclair talks about how, even before people noticed, the revolution had been wafting into homes across America via the music young people were listening to on the radio. That moment has passed, but Sinclair’s work—in poetry, in music, and in the places where they meet—never stopped. What he shows us, and what we’re able to see plainly in his six-decade career, is a consistent belief in a world re-makeable by art. The work is ongoing, and we can all take up the cause. The first step is to tune in. For his part, Sinclair tells me that now he is most of all “interested in what’s going to happen tomorrow.”

Rebecca Kosick co-directs the Bristol Poetry Institute and founded the Indisciplinary Poetics Research Cluster at the University of Bristol, where she is senior lecturer in comparative poetry and poetics. She is the author of Labor Day (Golias Books, 2020) and Material Poetics in Hemispheric America: Words and Objects, 1950-2010 (Edinburgh University Press, 2020), as well as editor-translator of H…