Federico García Lorca: “Dreamwalking Ballad”

Metaphor in Lorca is a form of gorgeous shorthand.

BY Sarah Arvio

Federico García Lorca had a great ability to tell ravishing and ravaging tales of love between men and women, and as a gay man he disguised his own passion for men in poems that include few personal pronouns.1 The love he described was almost always illicit, so maybe we can say that it stands in for his own illicit and illegal desire.

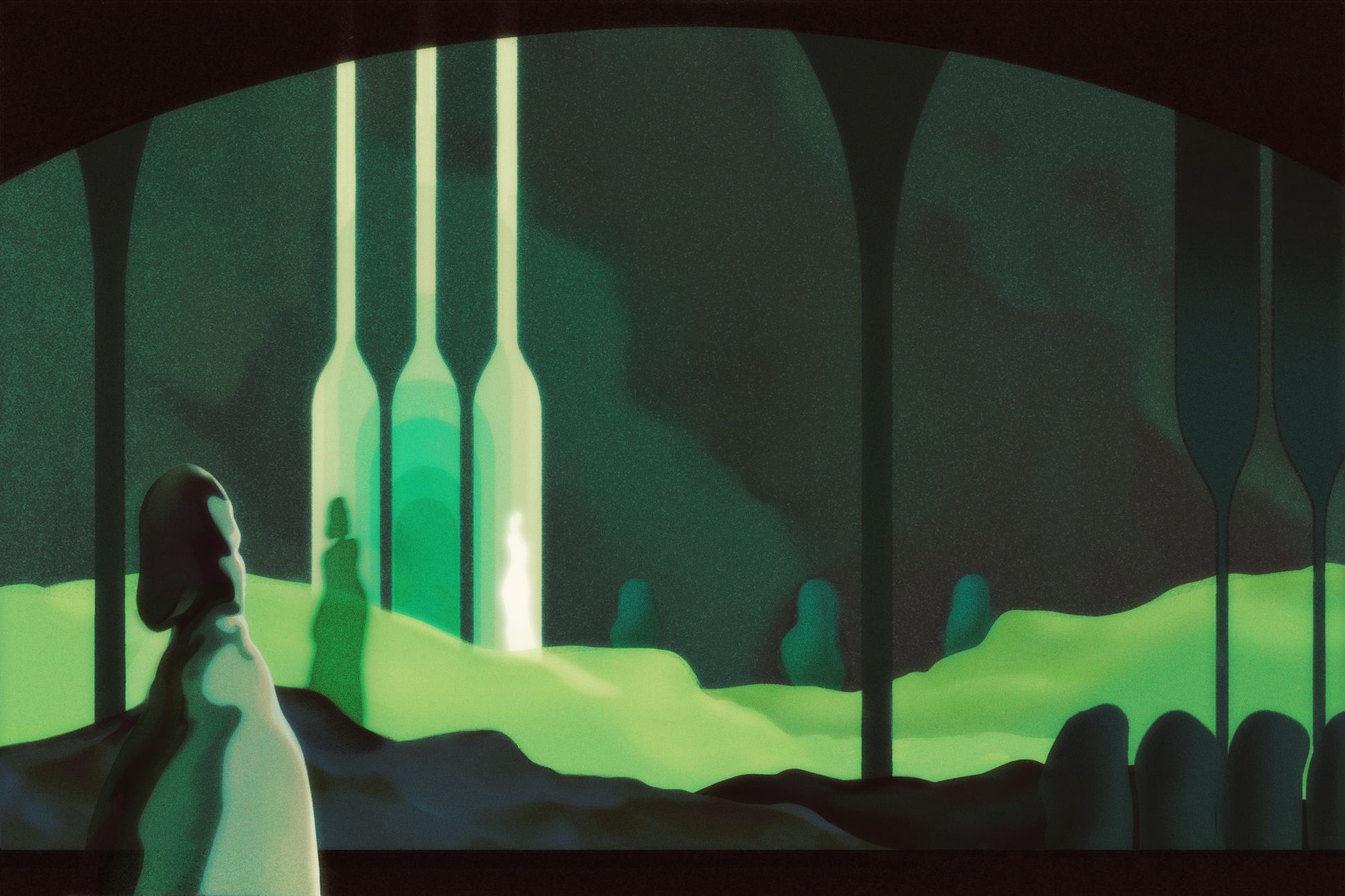

Lorca’s first great love poems appear in Gypsy Ballads2. One of these is “Romance sonámbulo,” which I translate as “Dreamwalking Ballad.” Somnus is Latin for “sleep”; in Spanish, the word sueño names the act of sleeping or dreaming; ambular means to walk. Walking in a dream. The poem not so much describes as enacts a dream state that is both terrible and beautiful.

What makes it a dream or like a dream?

The poem is framed with a refrain that repeats and changes, and each time it changes, it deepens. The refrain tells us about the greenness of desire. “Green I want you green” (“Verde que te quiero verde”)—exotic, fresh, and full of longing. The line never loses its sparkle or the plunge into a green night of the repeated verde and verde. What makes green sexy, I wonder; the words green and sexy aren’t natural friends.

The story focuses on three people who are part of a tragedy that is never fully explained. The refrain is woven into their voices, or the voices are woven into the refrain, which may be like the chorus of a Greek tragedy that alludes to the facts of the tragedy without spelling them out. Lorca read widely in world poetries, drawing inspiration for his poems.

The dream may be a modern-day “Kubla Khan,” with the green refrain played on the dulcimer. Samuel Taylor Coleridge called his poem a “vision in a dream”; it’s known that he wrote it in a drugged state, under the influence of laudanum.

That with music loud and long,

I would build that dome in air,

That sunny dome! those caves of ice!

And all who heard should see them there,

And all should cry, Beware! Beware!

In the unseen distance, there is a “Boat on the sea” and a “horse on the mountain.” These are means of escape, though all three know there is no escape. The “dream of the bitter sea” is the gypsy girl’s drama.

Lorca’s ballads are folk tales and love poems and also a paean to his friends, the dark-skinned gypsies3—historically maligned by Spanish society—who made their home and strummed their guitars in his father’s fields.

But Lorca is not solely a love poet. He’s a poet of death and the fear of death. The mood, the tone, and the attraction to tragic sublimity are all his; there is no precedent even in the Spanish ballads he was emulating.

In “Dreamwalking Ballad,”—as in all his ballads—Lorca shuns narrative but never loses it. He doesn’t describe his characters, he evokes them, with a green night and blood on a shirt. His dream environment coheres. Who is this girl, who are these “compadres”? We know her flesh is green, her hair is green, and her eyes are cold silver. She reflects the leafy woods and the silver moon. It’s very cold. In Spain, a “compadre” can be an intimate friend or someone unknown to you; here, I feel that the word implies a sudden bond. There are two men, and they are climbing together to the green terrace.

One says to the other, “If I could, young friend”—so now we know that one is old and one is young. The young man’s chest is covered with blood roses; he is dying. He begs the older man to take his horse and his saddle in exchange for his life and his bed.

Compadre can I swap

my horse for your house

saddle for your mirror

knife for your blanket4

We don’t know the story of the girl at the railing on a green night or of the two men climbing to the green terrace, one whose chest is covered with blood, the blood of roses. We know that the young man with the blood roses on his chest asks the older man if he will take his horse, his saddle, and his knife in exchange for a decent place to sleep.

The older man replies, “I’m no longer me / my house isn’t mine.”

Could he be the one who stabbed the young man whose chest is covered with blood roses? Did the older man and the young man fight over the woman on the green terrace? Their voices weave together. It’s hard to tell whether both men, the young dying man and the older man, want to climb to the green terrace. The terrace becomes a kind of cold heaven, lit by the moon.

Both know that the young man will die and the older man will be apprehended; we know this, too. The civil guards are on their way, and at last they catch up to them. “Let me climb let me / to the green terrace.” Their fates are intertwined, but we don’t know how. The young man will die, and the older man will be taken away by the civil guards.

We know that she—the beloved—is crying at a railing and that the young man is dying. We also know that the blood roses on his shirt are of love blood. Metaphor in Lorca is a form of gorgeous shorthand.

Lorca was an empathic realist, maybe an Aristotelian realist—that universals exist in things. Or maybe he was cultivating something more like William Carlos Williams’s no ideas but in things, and he used his images to expand feeling and meaning. He was a poet of metaphor and rapture. He was a romantic, too, as the green foliage of the poem tells.

He, the poet, doesn’t say that the young man was mortally wounded because the girl on the terrace was loved by someone else, or that one of them stole her from the other… He tells us about the blood roses on the young man’s breast. The roses tell us, in turn, that this is not ordinary blood: it is the blood of love that comes to violence. The rose, after all, enchants us with its bloom and wounds us with its thorn.

Not to be glib—this is Lorca’s life story and recurring premonition. As a young man, he often enacted death scenes—rehearsals of his own death—he played dead—with his friends as cast members. We know from a police report written many years after his murder, and divulged again many years later, that he was taken away and shot for being a “homosexual” and a “socialist.” Those are the words. His was a political murder. He was killed for the love of humanity and for the love of men.

Being murdered for your love proclivities does mean that you have shed love blood—the blood of roses.

The refrain is not only a recurring song, it’s a lament. Green is the color of leaves and reeds and grass. The changing parts of the refrain add to the swirling effect, one line coming in, two lines, one. The word verde—green—introduces the refrain; we always know which lines are the refrain because of the rhythm that is set up in the first line of the poem and picks up again each time the word is intoned.

Note the repetition of the GR’s in the word green, which do something like the R and D of verde. This is a half-rolled R followed by the TH sound (which is the pronunciation of the Spanish letter D). “Green I want you green / green wind green branches.” The passion is carried within the casing of the refrain.

Green I want you green

The great stars of frost

come with fish of shadow

paving the path to dawn

Stars of frost? If you have looked at frost on leaves, you know that frost twinkles at daybreak when the grass is deep and wet from dew. And shadows, don’t they suggest the shape of fish, perhaps the shadows moving under trees when dusk is falling? The next line suggests that shadows also resemble paving stones: “paving the path to dawn.” The linked shadow-fish, which are also flagstones, show the way to dawn.

Three lines later appears one of Lorca’s most exquisite and recherché images, “the wildcat mountain / bares its sour agaves.” Do you see that agaves, those succulents with spikes reaching toward the sky, resemble a hand or a paw held upward baring its claws? The poet’s imagery, though it comes to him in a lyrical free fall, is so precise.

Lorca had an impeccable ear for form, which he wrote with ease, never shirking a syllable. These stories peopled by gypsies are written in traditional Spanish ballad. Sixteen-syllable sentences fold over to make couplets of two lines of eight, with a rhythmic pattern of two or three stresses, and the sentence ends where the second line ends. The couplets are grouped into stanzas. These are fast lines, they ripple forward. As Alexander Pope taught us, the fewer the stresses, the faster the line. With the form, Lorca is saying—he is always saying many things at once—that the gypsies are Spanish, too, and thus they deserve some ballads.

Throughout the poem, voices weave in and out of the narrative and flow into each other, enhancing the sense of dreaminess. The refrain seems to reflect the desires of all three voices.

The young lover asks the older man if he sees the slash from his breast to his throat. The older man replies that the younger man’s blood stinks in his sash. One or both say, “let me climb let me / to the green terrace.” The terrace is where the girl is waiting. The civil guards catch up with them; they are drunk; the game is up. Neither man will reach the high terrace. The refrain weaves in and out. “Railing of moonlight / and the rushing water.”

The question has been asked: is this poem surreal5? I’m not sure the answer matters. The answer may be yes, but only in the adjectival meaning of “more real than real,” and in the dreamlike description of the setting, which mingles with the logic of the narrative. It’s interesting to consider that the word surreal doesn’t exist in Spanish. Surrealismo is a borrowing from the French surréalisme. The word comes to us from the French surréel = qui dépasse le réel: that which goes beyond the real—as a dream does.

André Breton had announced the founding of a movement to be called surreálisme in 1924. Lorca, then only 26, began Gypsy Ballads that year. He surely had read Breton’s manifesto, or had heard enough about it to hurry ahead. But he borrowed only what he liked: the dream. By nature he was a realist, and his gorgeous oneiric passages seek exactness of description and empathy and also meet the demands of narrative—even if not all the facts are known. I’ve analyzed the poem all the way through, and now I think I should start again. Dreams, like refrains, return and return.

And what do we think of the moon icicle hanging above? It’s surely a spike of light. It also tells us how cold it is: the cold of the night and the cold of the suffering human spirit.

Footnotes:

1. Homosexuality was not decriminalized until 1979 in Spain with the reformation of Franco’s “Law on Social Danger.”

2. El primer romancero gitano—Gypsy Ballads—or “the first book of gypsy ballads”—was written in the late 1920s, followed by the great gacelas and casidas of The Tamarit Diwan and the great Dark Love Sonnets. See my translations in Poet in Spain (Knopf, 2017).

3. The word gitano (“gypsy”)—which describes the people now formally referred to as Roma—is still in use in Spain, and is not felt to be derogatory except when used in a hostile way. I feel that gypsy is the truer and earthier word—the word that the Spanish gypsies use to refer to themselves—and have retained it for the sense and music of the poem. Gypsy derives from the word Egyptian, which came into English from Middle French in the early 16th century, and refers to the darkness of their skin. On the other hand, the word Roma (from Sanskrit domb or domba) refers to their designation as low-caste musicians in the Hindu caste system. In my view, gypsy is the more satisfactory choice.

4. The unstressed last syllable of the Spanish ballad line, which is often a vowel, swings us forward to the often-stressed first syllable of the next line. This is so unlike the masculine end rhyme preferred in English verse: here, the rhyme word ends with a vowel. I notice that I have emulated Lorca’s flow-through effect by ending many of my lines with unstressed “feminine” syllables. The first words of most of my lines are trochaic (meaning that the first syllable takes the stress), with one exception: Green, green, boat, horse, shadow, [she], Green, Under, things, but. “She” is the exception.

5. The surrealist-motivated Poet in New York and the also surrealist Odes were stylistic excursions, as were all of Lorca’s poem sequences.

References:

Aristotle’s “theory of universals”

André Breton, Le Manifeste du Surréalisme, 1924

Samuel Taylor Coleridge, “Kubla Khan”

Alexander Pope’s poem, “An Essay on Criticism”

William Carlos Williams, Paterson

Sarah Arvio has published three books of poems: Cry Back My Sea (Knopf, 2021), Sono: cantos (Knopf, 2006), and Visits from the Seventh (Knopf, 2002). She is also the author of night thoughts: 70 dream poems & notes from an analysis (Knopf, 2013), a hybrid book of poetry, essays, and memoir; and Poet in Spain: New Translations, a book of translated poems and a play by Federico García Lorca (Knopf, …